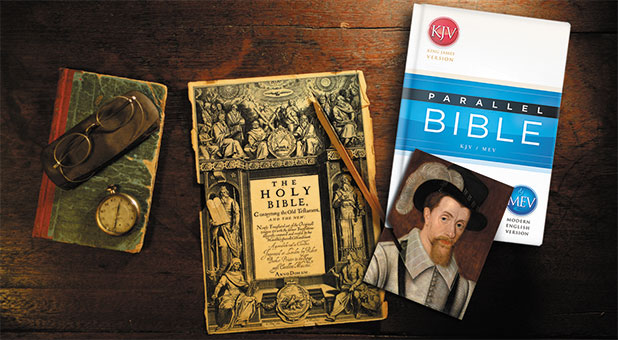

When it comes to Bible translations, I’m not too picky. Go ahead and argue why your favorite is better than all the others; at the end of the day, I adhere to the old saying: The best translation is the one you will read. Yet there is one version of the Bible that has a special place in my heart and on my tongue: the King James Version (KJV).

There are certain Bible passages I will always prefer in the poetic cadences of the KJV. When I pray the Lord’s Prayer, I don’t ask God to forgive my sins; it’s my “trespasses.” When I recite Psalm 23, I don’t merely go through a “dark valley”; I walk “through the valley of the shadow of death.” And when I read the Sermon on the Mount, I will always hear Jesus commanding His disciples to “seek ye first the kingdom of God.”

I’m not the only one fond of the famous translation. A recent report from the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture found that the KJV is still the most popular translation for Americans: 55 percent of Bible readers use the KJV—more than double the percentage that opt for the New International Version, the second-most popular Bible.

However, there are signs that the KJV is losing ground with the younger generation. A poll conducted in 2010 for the 400th anniversary of the creation of the KJV found that the majority of those under 35 in the United Kingdom—the birthplace of the KJV—hadn’t even heard of the translation.

I lament this loss, but understand it. Though I love the lyrical elegance of the King James, I don’t reach for it at devotion time. The archaic language is beautiful, but daunting. All the “thees” and “thous” trip me up. I end up spending as much time trying to understand the words as I do pondering their meaning.

That’s why I was excited to hear about the Modern English Version (MEV), a new translation, out this month, that seeks to maintain the poetic quality of the KJV “while providing clarity for a new generation of Bible readers.” The scholars behind the MEV aimed to produce a translation that was both beautiful and accurate.

Reworking a Masterpiece

It would be difficult to overstate the impact the King James Version has had on the world. Winston Churchill called the KJV an “enduring link, literary and religious, between the English-speaking people of the world.” Compton’s Encyclopedia describes it as “one of the supreme achievements of the English Renaissance.” To date it has sold more than 1 billion copies. It has shaped our spiritual and linguistic reality. Many of the most vibrant expressions of the English language are lifted from its pages. Whenever you bite the dust, fall from grace, go the second mile, rise and shine, or see the writing on the wall, you pay homage to the literary masterpiece commissioned by King James I more than 400 years ago.

Updating a work of such momentous importance is a formidable undertaking. It’s a fact not lost on Rudolph Gonzalez, one of the New Testament scholars who worked on the MEV.

“The KJV is a masterpiece,” he says. “It’s like someone handed you a Rembrandt or da Vinci. You want to work on it with extreme care, reverence, even fear and trembling. And that’s exactly what I did.”

Gonzalez described the goal of the translators as being twofold: “Render a fresh, modern translation while at the same time preserve a reading experience that echoes the elegance of the KJV.” To describe these twin goals, Gonzalez turned to Scripture. “I like to think of what we did in terms of the scribe Jesus commends in Matthew 13:52, who ‘brings forth treasures both old and new.’ That’s what this translation is meant to do.”

Blake Hearson, who headed up the Old Testament translation, explains the role the KJV played in the creation of the MEV: “We wanted [the MEV] to feel familiar, like home for people who are used to the KJV,” he says. “It’s been more than 30 years since the New King James Version was published, and the English language changes so quickly.”

At the same time, Hearson underscores the importance of rendering an accurate translation. “We used both the KJV and the original languages as our basis,” he says. “We used the best original manuscripts available, including the Textus Receptus and the Hayyim Edition of the Hebrew text [the foundational texts for the KJV].”

Scholars who worked on the MEV were intentionally drawn from a variety of denominations and traditions from around the globe. Each came with their own worldview, yet part of the MEV’s uniqueness is the dedication the team had to omitting any cultural, social or political bias (something that hasn’t always been the case with recent translations).

Jason McMullen, publishing director of the MEV, says the team’s devotion to Scripture and to Christ during this process was the core factor behind every translated word. “This was put together by scholars who are not only great at their craft, but who have a personal relationship with Jesus and who depend on the power of the Holy Spirit in their everyday lives,” he says.

The result is a tranlation that retains the beauty of the KJV while removing archaisms, all through subtle changes that often go undetected to the casual reader but will be deeply appreciated by students of the Word.

“I feel like we kept the flow of the KJV but produced a translation that is more faithful to the text,” Hearson says. “The thees and thous are gone, but we were able to preserve the cadence and meter.”

Finding Fresh Eyes

The goal of the MEV extends beyond giving current KJV readers a more accessible Bible, however. Gonzalez is eager to see the MEV connect with new readers, and this was another core driving force for the entire team.

“My prayer is that this translation will help young people stay in touch with these documents that were so foundational in church history,” Gonzalez says. He also hopes it will reach an international audience. The KJV, carried around the world by missionaries for centuries, was instrumental in making English a global language. Now Gonzalez hopes the MEV will connect with English-speakers abroad.

“There are English speakers almost everywhere,” he says. “So I think this translation has the potential to cross oceans. It can definitely transcend a Western context.”

Hearson hopes the MEV will boost Bible reading. “Biblical illiteracy is growing. It’s a huge problem,” he says. “If people have a familiarity with the Bible, it’s usually with the KJV. But the KJV is hard to understand.”

That’s where Hearson believes the MEV can help, by providing a link between the past and the present. “The MEV is understandable but familiar. It feels like Scripture.”

Hearson points out that the original inspiration for the MEV came from military chaplains seeking a more accessible translation. In early 2005, James Linzey, a retired U.S. Army National Guard chaplain and graduate of Fuller Theological Seminary, recruited 47 scholars to accomplish this goal of a new Bible translation that could be used on the battlefield. Now the MEV’s chief editor and chairman of the translation committee is hopeful it will be used by soldiers and in other frontline contexts all over the world.

“My ultimate goal for this translation,” Hearson says, “is that it will inspire people to seek God and know Him more.”

A New History

With biblical literacy declining in America yet Bible publishers churning out new custom versions for everyone from gardeners to patriots to young moms, why does the world need another translation? And why now?

To answer this question—one the MEV’s creators certainly posed as well—requires some historical and cultural context. The truth is, Bible translation has played a pivotal role throughout church history. And new translations have always been born out of a practical necessity—to give people God’s Word in a language they could understand.

The New Testament was originally written in Koine Greek, the “common” language of the day. In the late fourth century a priest and theologian named Jerome produced the Latin Vulgate, the translation that became the Western’s church’s official Bible for more than 1,000 years.

In 1522, Martin Luther created the first Bible translation in a European language. His German translation was met with massive resistance. For many it was unthinkable to replace the esteemed Vulgate. But the irony of history was lost on his opponents. Vulgate was simply the Latin word for “common.” The hallowed Latin Vulgate was written in the everyday language of Jerome’s day; Luther was merely following suit. Yet by Luther’s time, only the clergy could read Latin. A new translation was needed so the people could read the Scriptures in the German vernacular.

Likewise, the KJV’s creation was another chapter in the story of bringing the Bible to the people. Prior to the 1611 King James Bible, most churches did not have Bibles. The ones that did possess Bibles often chained them down to protect them from thieves.

In addition to addressing this shortage of Bibles, the KJV was intentionally accessible. King James instructed the scholars selected for the task of translation to select verbiage that would feel familiar to readers and listeners. Even the KJV was not meant to replace but improve upon older translations, specifically the Church of England’s official Bishops’ Bible. In a preface of an early printing of the KJV, the translators wrote that their goal was not to replace the Bishop’s Bible, but “to make a good translation better.”

Make a good translation better. That’s precisely what the creators of the MEV set out to accomplish. They’ve produced a translation that preserves the rich experience of reading the KJV while making the Scriptures clear and accessible to contemporary readers. In doing so, they join a holy procession of translators who throughout history have toiled to make the Bible accessible to as many people as possible. It’s a difficult undertaking, but a needed one, perhaps in our time more than ever. And if history repeats itself, this new rendering of God’s Word just might echo in the hearts and minds of people for generations to come.

Drew Dyck is the managing editor of Leadership Journal and author of Yawning at Tigers: You Can’t Tame God, So Stop Trying.

Watch a Bible scholar use examples in Scripture to explain more about what makes the Modern English Version unique at mev.charismamag.com