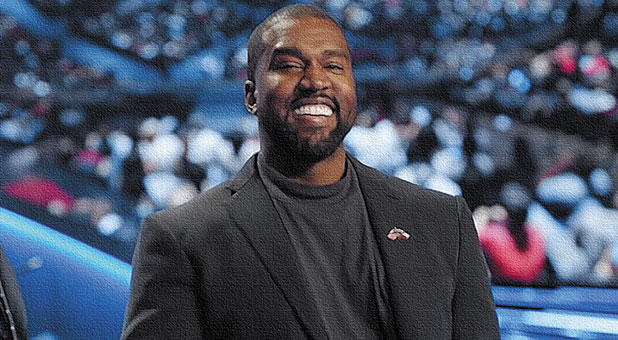

On Oct. 25, 2019, bestselling rapper Kanye West released Jesus Is King, his ninth studio album overall but his first as a self-described Christian artist. From beginning to end, the album is about his relationship with Jesus, his joy at being saved and his awe for the God who loves him. The album is profanity-free and features no sexual or violent content.

Jesus Is King immediately triggered strong and polarized reactions. Many conservatives and evangelical Christians exuberantly expressed their love for the album. In a column for National Review, Andrew T. Walker breathlessly said West possessed “the anthropology of C. S. Lewis, the economics of Wilhelm Röpke, the cultural mood of Wendell Berry and the defiance of Francis Schaeffer.”

Meanwhile, longtime fans of West expressed their frustration, calling the lyrics corny and West an attention-seeker. The Daily Beast ran a headline calling Jesus Is King “fake Christianity at its finest.”

Even some Christian leaders expressed skepticism toward West’s sudden pivot into Christian music—including Tyler Burns, a Pentecostal pastor featured in last month’s “Tomorrow’s Charismatics” feature. Burns, writing for The Washington Post, noted that West appropriated the sound of gospel music while discarding the theology of the black church that is meant to accompany it.

He concluded, “While Jesus Is King feels like it should be a cultural moment of celebration for all Christians, it should come as no surprise that many black Christians question who this moment will ultimately empower.”

West’s Christian faith has only continued to dominate news headlines since Jesus Is King‘s release. The album hit No. 1 on Billboard charts during its debut week. West has spoken and performed at Joel Osteen’s Lakewood Church. In January, West replaced comedian John Crist as the headliner at the Strength to Stand Student Bible Conference in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, alongside Hillsong Young & Free. Over the span of 2019, West went from the artist who released the blasphemous album Yeezus to a bona fide Christian celebrity, in some cases being treated with the authority of a leader.

Naturally, such a drastic transformation also sparks many questions:

Is Kanye for real?

Will his conversion stick?

And should such a young, immature Christian ever be given so much authority and access to major platforms?

In fact, believers who only recently began paying attention to West may be surprised to learn he’s been wrestling with God his entire life. Though unlikely to assure those doubting West’s sincerity—and ultimately, West’s faith is between him and God—this story will review West’s long and troubled relationship with Christianity over two decades in the public eye.

Jesus Walks

By all accounts, West was raised in a Christian household and could be considered at least a nominal Christian for most of his life. While speaking with Osteen at Lakewood Church, West shared that he grew up going to church “three times a week,” thanks to his father.

“For me as a kid, going to church on Wednesday instead of going to basketball practice or getting to play video games got to be a little bit boring,” West says. “My mom had me in church twice a week, definitely on Sundays. We actually grew with the church; it was a pastor named Johnny Coleman, and we grew from a small church to a megachurch—a Chicago version. I think it grew to like five or six thousand [people]. My mom always had the records in the house, and we would be playing a lot of R&B records, but then we’d go and hear the gospel and hear worship.”

In January 2009, West told Bossip his father scared him straight when he thought about leaving the Christian faith.

“I had a conversation with my dad when I was 20 years old and [said], ‘I don’t believe in this everybody’s going to hell thing [where] everyone who isn’t a Christian is in the wrong,'” West says. “His response at that time was, ‘Well, I’d hate to see you not spend eternity with me and burn in the depths of hell.’ I was like, ‘Well … I don’t want that to happen, so let me set up this insurance plan and just do this.'”

In February 2004, West released his first album, The College Dropout. He released the single “Jesus Walks” to radio that December. The song samples ARC Choir’s “Walk With Me” and features West rapping about his own sins, his struggles to talk to the Lord and how Jesus walks alongside “the hustlers, killers, murderers, drug dealers, even the strippers” and loves them. He says industry executives say you can rap about “guns, sex, lies, videotape. But if I talk about God, my record won’t get played, huh?”

On the chorus, West pleads, “God show me the way because the devil’s trying to break me down/ The only thing that I pray is that my feet don’t fail me now/ And I don’t think there’s nothing I can do now to right my wrongs/ I want to talk to God but I’m afraid cause we ain’t spoke in so long.”

Though the song features strong profanity, it was the first tease that West was interested in using music to explore the faith of his childhood.

The song was an early hit, peaking at No. 11 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts and later winning the Grammy Award for best rap song. Rolling Stone called “Jesus Walks” the 19th best song of the decade.

Despite this success, West’s faith would mostly stay buried on his next few albums—though he continued to talk about Christianity in media interviews.

“I will say that I’m spiritual,” West told The New York Times in June 2004. “I have accepted Jesus as my Savior. And I will say that I fall short every day.”

Controversially, in 2006, West posed for Rolling Stone magazine wearing a crown of thorns. “The Passion of Kanye West”—as the feature was titled—ironically spoke very little of his Christian faith, other than West invoking it as the reason behind his calls to end homophobia in the hip-hop scene. West said, “I knew there would be a backlash, but it didn’t scare me, because I felt like God wanted me to say something about that.”

On Nov. 10, 2007, West’s mother, Donda, died of complications following a cosmetic surgery operation. Her death devastated West and changed his outlook on life in many ways—and that included his faith. In 2008, West told The Fader, “I’m like a vessel, and God has chosen me to be the voice and the connector.”

But by January 2009, West was distancing himself from Christianity. In an explosive interview with Bossip, West said he respected the Christian faith, but it had been forced upon him as a child.

“Christianity wasn’t an option when I was growing up,” West said. “It was the only thing. It wasn’t like I was given the decision at the time. You know how you decide that you want to be a doctor or a lawyer or a painter or a basketball player or whatever? You’re not given a decision of what religion you want. Your parents just give it to you. Like, you’re a Jew or you’re a Muslim or you’re a Christian. I feel like religion is more about separation and judgment than bringing people together and understanding.”

Later, he added: “I believe in Jesus as an icon, but I don’t feel the responsibility to put my life on Jesus. I feel I need to take responsibility for my own successes and failures. Why I say, ‘I don’t give it all up to Jesus’ is because there are a lot of people who don’t take responsibility for their lives and always think Jesus is going to handle it. And that’s what I refuse to do.

“Christianity is embedded in who I am, so I will still say things like ‘This is a blessing,’ ‘Amen’ and still say prayers; things that your grandmother embedded in you. I’m always going to have a little Chicago in me, a little ‘hood in me and a little Christianity in me. Just because it’s what I know. But I do not believe that other religions are going to hell. I do not believe in a lot of elements of it.”

He also said that “Jesus Walks” may have reflected how he felt in 2003, but six years later, his views had changed and “this is how I feel now.” He promised he would always be honest about what was going on in his personal life. He crassly explained that if he were a Christian preacher, he wouldn’t be secretly attending strip clubs; he would openly tell the church onstage that he was seeing prostitutes.

“After my mom passed, it wasn’t a thing where I lost my mind or anything,” West told Bossip. “I was less scared to speak my mind. Cause there’s nothing I could lose. There’s nothing that could be taken away from me. … Religion is like clothing. People want comfort. People don’t want to have to take that off. People don’t want to accept the concept of there not being a heaven possibly, or the concept of losing someone and not seeing them again. The only thing that keeps you going is the idea that you will see them again.”

Soon West’s music started to engage with religion again, but in subversive ways. On “No Church in the Wild,” a single featuring West and Jay-Z, the chorus declares, “What’s a mob to a king?/ What’s a king to a God?/ What’s a God to a nonbeliever who don’t believe in anything?”

West—often nicknamed “Ye” or “Yeezy”—titled his 2013 album Yeezus and recorded a song titled “I Am a God.” West repeatedly asserts his own godhood throughout the song—it’s unclear whether he is being literal or ironic—and at one point pictures a blasphemous encounter with Jesus.

“I just talked to Jesus,” West raps. “He said, ‘What up, Yeezus?’/ I said … ‘I’m chilling/Trying to stack these millions.’ I know He the Most High/ But I am a close high.”

Yet paradoxically, West also began reasserting the strength of his Christian faith while producing and later touring this album.

In a 2013 interview, West wore a WWJD bracelet—which stands for “What Would Jesus Do?”—and said, “I’m a Christian, and I wanted to just always let people know that that’s what’s on my mind. It’s important to me that I grow and walk and raise my family with Christian values.”

At a 2014 concert, Kanye shouted, “I’m a married, Christian man!”

West shocked many when he announced his next album—2016’s The Life of Pablo—would be a gospel album. He even worked with Kirk Franklin on the album.

At the time, Franklin received flack for the decision to work with West. He defended himself on Facebook, writing, “I will not turn my back on my brother. I will love him, prayerfully grow with him. However long he’ll have me, and however long the race takes. To a lot of my Christian family, I’m sorry he’s not good enough, Christian enough or running at your pace.”

The problem, as West later explained at Lakewood Church, is that he didn’t understand what it really meant to make a gospel album—and lots of people in his life were enabling him in the wrong ways.

“I didn’t know how to totally make a gospel album,” West says. “And the Christians that were around were too, I would say, beaten into submission by society [to] speak up and profess the gospel to me, because I was a superstar. But the only superstar is Jesus.

“…Even for someone who’s professing God and saying, ‘This is going to be a gospel album,’ the devil’s gonna come and do everything he can to distract people from knowing how to fully be in service to the Lord.”

In a 2019 video with James Corden, West says many people were praying for him during this season of life, but his heart was closed to God.

“It was people in my family who were praying for me, but they couldn’t call me and scream at me,” West says. “I’m a grown man. I made my own mind. I actually made it this far by not listening to anybody. So I don’t want advice from people. But it’s God who came and put this thing on my heart and said, ‘Are you ready to be in service to Him?'”

Selah

West says everything changed for him when he was admitted to the Medical Center at the University of California-Los Angeles following a nervous breakdown. On Nov. 20, 2016, West ended a concert prematurely after alleging that Jay-Z had “killers” who were coming after West. He pleaded onstage, “Jay-Z, I know you got killers. Please don’t send them at my head. Just call me. Talk to me like a man.” He also rambled about Beyonce, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and DJ Khaled.

The next day, he was voluntarily persuaded by authorities to check himself into the UCLA Medical Center for hallucinations and paranoia. According to multiple sources, factors that may have contributed to West’s breakdown include drug addiction, depression and anxiety, suicidal ideation and lingering trauma after the death of his mother. He was released from the hospital on Nov. 30.

“I know that God’s been calling me for a long time, and the devil’s been distracting me for a long time,” West told Osteen. “When I was at my lowest point, you know, God was there with me and sending me visions and inspiring me. I remember sitting in the hospital at UCLA after having a mental breakdown, and there’s documentations of me drawing a church and writing, ‘start a church in the middle of Calabasas, [California].'”

That was the original seed for what would become Sunday Service—informal West-led performances of gospel music, Christianized secular music and even occasional preaching—in early 2019.

“When I started Sunday Service, I started my church,” West says. “People told me I could [not] call [it] a church because ‘you ain’t got no pastor, so it ain’t really a church.’ But it was church for us. It was all we had. We didn’t really have a place to consistently go every week and bring the family, and we started off by just having … nice, easy-to-listen-to records and good feelings. I had a friend who came by and said, ‘But you have to say the name Jesus. You can have all of this good-sounding stuff, but eventually people are going to need solid food.’ So we started to then incorporate that.”

West reportedly has close pastoral relationships with Pastor Rich Wilkerson Jr. of VOUS Church in Miami, Florida, and has been mentored by Pastor Adam Tyson of Placerita Bible Church in Santa Clarita, California. Wilkerson officiated West’s wedding to Kim Kardashian, and Tyson has preached at many of the artist’s recent Sunday Services. West says at night, he sits and reads the Bible by himself.

Today West says he views himself as a work in progress and is not ashamed of his past, telling Corden, “The only thing that could be perfect is God’s plan.”

Kardashian and others close to West insist his transformation is genuine. Even Corden riffed, after a long interview on an airplane with West, “I don’t know if it’s the plane or the altitude or just because we’re in the sky, but I am starting to feel closer to God. I’ll be honest.”

And ultimately, West believes God led him through this entire process for a reason.

“God’s always had a plan for me,” he told Corden. “He always wanted to use me. But I think He wanted me to suffer more and wanted people to see my suffering and see my pain and put stigmas on me and have me go through all my experiences—the human experiences. So now when I talk about how Jesus saved me, more people can relate to that experience. If it was just, ‘Oh, we grew up with this guy’s music and now he’s a superstar,’ it’s less compelling than, ‘Oh, this guy had a mental breakdown, this guy was in debt.'”

Sing About Me

Plenty has been written about what West’s recent behavior says about him. But what does our reaction to him say about us?

Many rejoiced over West’s radical conversion, but the story didn’t stop there. Headlines about West have continued to dominate Christian news outlets for months since. Some observers have asked a good question: Why did West’s conversion receive so much more attention than other rappers who embraced Christianity?

After all, West’s story is not unique. Writing for The Washington Post, Esau McCaulley—an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois—wrote about the long intersection of Christianity and rap music.

“At the height of the Bad Boy Records era, Mase left hip-hop to begin life as a pastor,” McCaulley says. “Snoop Dogg released a gospel album. Tupac Shakur declared that only God could judge him. DMX and Chance the Rapper have been vocal about their faith in Jesus. Kendrick Lamar’s two most recent albums have wrestled with issues of faith.”

Consider two of the most recent examples. Back in 2012, Lamar was rapping about heaven, hell, his own songs and his need for redemption: “What if today was the rapture and you completely tarnished? The truth will set you free, so to me be completely honest/ You dyin’ of thirst, you dyin’ of thirst/ So hop in that water, and pray that it works.” The 12-minute song—”Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst”—concludes with a literal sinner’s prayer. Lamar’s 2017 follow-up had Christian and secular outlets alike raving; NPR called the album a “prophetic struggle,” while Christianity Today’s Matthew Linder wrote that Lamar “consistently envelopes his narratives of hope and despair within overtly Christian language and theology.”

Likewise, Chance the Rapper’s 2016 mixtape Coloring Book—which won the award for best rap album at the 2017 Grammy Awards—is loaded with Christian lyrics. Chance raps about “holistic discernment” that helps him resist the devil on the opening track “All We Got.” And on the song “How Great,” a reimagining of Chris Tomlin’s “How Great Is Our God,” Chance talks about “the type of worship [that will] make Jesus come back a day early, with the faith of a … mustard seed.” The track amazed Tomlin so much that he wrote on Twitter, “[Chance] took ‘How Great is Our God’ to a new level!”

Yet neither of those artists received the plaudits and attention West has received from Christian circles. Potential explanations are numerous. Perhaps West is simply the most noteworthy and famous rapper, or his testimony the most radical. Perhaps Chance and Lamar’s explicit lyrics on some songs make certain believers doubt the Christian truths they espouse on other tracks. Some have even cynically suggested that perhaps white evangelicals—81% of whom supported U.S. President Donald Trump in the 2016 election—were eager to accept West as one of their own, since he had spent the previous two years befriending and promoting Trump and disparaging liberals. In all likelihood, the answer is probably a combination of these factors and many more.

In his Washington Post column, Pastor Burns noted that West’s new theology appeals more to the sensibilities of white evangelicals than black Christians. The reasons are complex. To these brothers and sisters in Christ, West’s fraternizing with influential conservatives and leaders like Jerry Falwell Jr., Trump and Osteen is not seen as simply unity and fellowship among Christians; rather, they view it as flocking to power and abandoning the marginalized and the “least of these” who used to make up a substantial portion of his fanbase. To make that change while using gospel music can feel at best like ignorance and at worst like an insult.

“Can Kanye claim the music of a community if he appears unwilling to learn from their whole experience?” Burns writes. “A group of people who have been oppressed by a gospel that was designed to liberate will inevitably have trust issues. … Despite building his album around the transformative sound of gospel music, the robust theology that makes the black church a beacon of hope for the marginalized has been glaringly absent from Kanye’s lyrics and life. A conversion story so closely aligned with powerful people feels discordant with gospel music, a genre designed to cope with the weight of life’s most difficult trials.”

He concludes that “Black church choirs do not simply perform into empty vacuums just to uplift with beautiful harmony. Singing ‘God is the joy and the strength of my life’ is not a rally cry for earthly success; it is a plea for sanity and survival. Ultimately, the sound of freedom rings hollow without the God of the oppressed.”

Some may disagree with the force of Burns’ argument, while others might prefer to avoid such discussions altogether. However, this is a complicated subject that must be considered, given West’s decision to express his newfound faith through a genre with significant racial and cultural baggage.

In trying to make sense of West’s political and musical decisions, McCaulley ultimately saw similarities between West and the tax collectors of Jesus’ day.

“For some black people, West’s comment that ‘slavery was a choice’ when linked to his support of the current administration makes him something of a modern-day tax collector, belonging to a group of people who we should instinctively reject,” McCaulley says. “Therefore, any embrace of West involves joining arms with an administration associated with harm to many groups of people. Others are afraid that after West is welcomed into a church fold, he will say something controversial that brings shame on Christians or that he will grow weary of us and abandon us. We will look like pawns.”

Yet Jesus loved us anyway, without caring or fearing what shame we might bring to a church’s reputation or whether we were altogether healed. Thus, McCaulley says, we ought to extend that same love to West.

Yes, West’s faith is young, immature and potentially fragile. West has cited his net worth as proof of God’s faithfulness to him and at Lakewood called himself “the greatest artist that God has ever created.”

Yes, we should be wary about placing him in positions of spiritual authority before he has had time to mature—for his own sake more than our own. (The apostle Paul spent three years maturing and growing in his faith before entering ministry, according to Galatians 1:18.) That includes resisting the possible temptation to use West as a weapon in the culture wars, or his involvement at an event as free marketing for our ministries.

But if his conversion is genuine—and we have no reason to believe it is not—then he is our brother in Christ, and we should show him the love and grace God has shown us.

“We shouldn’t expect someone new to this level of devotion to spark a sudden revival,” McCaulley says. “We should not expect him to lead. We should instead give him space to learn, grow and be held accountable in a community of faith that will ground him and prepare him for a lifetime of service.”

Lecrae—perhaps the most successful Christian rapper to date, and one who is no stranger to these types of difficult conversations—may have phrased it best. On the day Jesus Is King released, Lecrae wrote on Twitter, “Regardless of how you feel about Kanye West, the content is refreshing to hear. God will get His glory. And Jesus is King.” {eoa}

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: If you liked this story, you can read more about the intersection of Christianity and pop culture at culture.charismamag.com.

Joshua Olson is a freelance writer for Charisma magazine.

CHARISMA is the only magazine dedicated to reporting on what the Holy Spirit is doing in the lives of believers around the world. If you are thirsty for more of God’s presence and His Holy Spirit, subscribe to CHARISMA and join a family of believers who choose to live life in the Spirit. CLICK HERE for a special offer.