Injustice moved the Motown artist to write “What’s Going On?” and activate his generation. Shouldn’t the church be doing the same?

The dawn of the 1970s was a time when life as many Americans knew it was rapidly changing. Widespread disenchantment with materialism and the American Dream of the 1950s had jolted the nation’s social consciousness. A generation of youth had found its revolutionary voice and was confronting oppression domestically and abroad.

The country was divided over a war on foreign soil, there was social decay at home between young and old, and racial tension simmered from the injustice of civil rights violations. It was as if current events were conspiring against a generation.

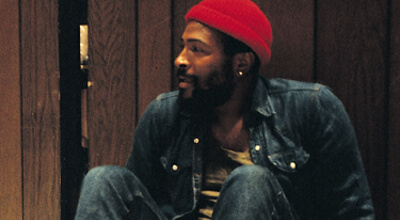

Amid this whirlwind of unrest Motown artist Marvin Gaye captured the ethos of the age with his 1971 song “What’s Going On?” It was an impassioned cry for justice in which he appealed to the nation’s conscience. The song didn’t fit the pop-music template, but Gaye was determined to release it anyway and was vindicated when the song landed at No. 2 on the Top 40 charts in 1971.

“Mother, mother, there’s too many of you crying,” Gaye sang. “Brother, brother, there’s far too many of you dying / Father, father, we don’t need to escalate / War is not the answer / For only love can conquer hate / Picket lines and picket signs, don’t punish me with brutality / Talk to me, so you can see / We’ve got to find a way to bring some lovin’ here today.”

Fast-forward to 2010, and Gaye’s plea feels just as timely. The soundtrack of the ’70s is still speaking to us. We’re asking: “Where’s the lovin’ here today?”

Where’s the lovin’ in the church’s music? Where’s the kind of lovin’ that rights wrongs and reconciles relationships in our world today?

Our generation has markings similar to Gaye’s generation—war, genocide, street gangs, ethnocentrism, generational poverty, famine, AIDS, substandard housing and education, rampant materialism, religious hatred, environmental degradation.

Because the gospel is the story of a loving God who reconciles people into a loving relationship with Himself and one another, justice fits into His story as Christ rights the wrongs that prevent those relationships. Worship, whether as music or lifestyle, should reflect this facet of Jesus’ mission.

Our Story or His Story

Too often instead our worship is directed inwardly and turns into a distorted, selfish facsimile. Our songs long for God to meet personal needs and mediate justice on our own behalf. Many of them have been radically reduced to individualized laundry lists of wants. Consider these lyrics from popular contemporary worship songs:

- “I can feel [the presence] [the Spirit] [the power] of the Lord / And I’m gonna get my blessing right now.”

- “In my life I’m soaked in blessing / And in heaven there’s a great reward / As for me and my house, we’re gonna serve the Lord / I’ve got Jesus, Jesus / He calls me for His own / And He lifts me, lifts me / Above the world I know.”

- “(I got the) anointing / (Got God’s) favor / (And we’re still) standing / I want it all back / Give me my stuff back / Give me my stuff / Give me my stuff back / I want it all / I want that.”

By contrast, three instances of “spoken-word lyrics” recorded in the Bible to accompany Jesus’ birth read much differently. They reverberate through history.

- “He has put down the mighty from their thrones, and exalted the lowly. He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich He has sent away empty” (Luke 1:52-53, NKJV). What of the Rolls-Royce driving, private-jet flying, multiple-mansion dwelling, high-fashion wearing modern Christian profiteers? What about the good life to which their songs and sermons aspire?

- “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men on whom his favor rests” (Luke 2:14, NIV). The peace they sang of is shalom, and favor refers to “the year of the Lord’s favor” embraced within Christ’s mission (see Luke 4:18-19; Isaiah 61). More than the absence of strife, shalom is what the Prince of Peace came to re-establish. The condition of sin robs us of shalom, but Jesus’ justice restores it. When we attempt to co-opt Jesus’ favor as a rationale to get more affluence, we cheapen everything the gospel represents.

- “A light to bring revelation to the Gentiles, and the glory of Your people Israel. … ‘This Child is destined for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign which will be spoken against (yes, a sword will pierce through your own soul also), that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed’” (Luke 2:32, 34-35, NKJV). Not much of our contemporary touchy-feely hoopla here either.

Not one of these “songs” celebrates the themes that predominate in our weekly worship services. There is no mention of “me,” except in the context of calling and responsibility beyond oneself; no focus on “blessing,” except as it relates to our ability being empowered by God for blessing others; no pursuit of personal comfort—rather, the promise is given of a sword that will pierce one’s soul.

What Would Jesus Sing?

The soundtrack that accompanied heaven’s greatest lyrics—the Word made flesh (see John 1:14)—bears little resemblance to popular songs we sing in our churches. When Jesus came and lived among us, His manner of doing so invited shame and ridicule, not material bounty.

He lived among us as a child of poverty (born in a barn); political refugee (in Egypt); social pariah (survivor of a capital crime: unmarried pregnancy); ghetto immigrant (“What good comes from Nazareth?”); and blue-collar worker (carpenter) who was a subject of an imperialistic colonizer (Rome).

Many of the people whose lives He changed had lived unfavorably or unlawfully in their society. His friends and followers included Mary Magdalene (ex-prostitute), Matthew and Zacchaeus (ex-crooked bureaucrats and tax collectors), and Simon Peter (ex-insurrectionist and card-carrying member of a terror organization in Palestine).

If Jesus actually were to show up today at one of our stylized worship experiences, He might well sing a different tune, one that sounds more like the warning He gave His people through the Old Testament prophet Amos:

“I can’t stand your religious meetings. I’m fed up with your conferences and conventions. I want nothing to do with your religion projects, your pretentious slogans and goals. I’m sick of your fund-raising schemes, your public relations and image making. I’ve had all I can take of your noisy ego-music.

“When was the last time you sang to me? Do you know what I want? I want justice—oceans of it. I want fairness—rivers of it. That’s what I want. That’s all I want” (Amos 5:21-24, The Message).

If all God wants is oceans of justice rather than egocentric noise, then a broken world’s needs must reclaim center stage from our personal blessings during corporate worship experiences. In our churches, many of us remain mute on such issues as public repentance for neglecting the poor. Some of us have abandoned prophetic moments of opportunity in lieu of religious protocol.

Traditions That Count

But there is good news too. More and more music ministers today across traditions are giving voice to justice within worship services. Jason Upton (“Poverty”), Aaron Niequist (“Love Can Change the World”) and Derek Webb (“Rich Young Ruler”) are just a few.

Historically, some denominational traditions have embraced justice-oriented hymns and music. The song “O Healing River” (1964) is sung to inspire believers in organizations such as Ecumenical Advocacy Alliance (e-alliance.ch) that work to establish justice in various social contexts.

Contemporary Christian music pioneer Keith Green was an anomaly among evangelicals through the 1970s and early 1980s, writing songs that called Christians out and challenged the church to action, such as “Asleep in the Light”:

“Oh, bless me, Lord / Bless me, Lord / You know it’s all I ever hear / No one aches / No one hurts / No one even sheds one tear / … / Open up, open up / And give yourself away / You’ve seen the need / You hear the cry / So how can you delay?”

Jesus’ mission to bring good news to the poor, sight to the blind and liberty to the oppressed should define our worship, be it expressed in music or lifestyle. Music, because we feel it, penetrates our hearts and stimulates a response. It ennobles ideas, emotes passion and defines eras. Gaye’s opus reminds us of that.

Reflecting Christ’s purpose through our lives will require the courage to break free from convention, perceive the new things God is doing in our midst and zealously pursue them.

What’s stopping us?

Jeremy Del Rio is an attorney and consultant for youth development, social justice and cultural engagement. He is a co-founder of 20/20 Vision for Schools, a campaign to transform public education (jeremydelrio.com). Louis Carlo is associate pastor at Abounding Grace Ministries in New York City, adjunct professor at Alliance Theological Seminary, as well as a photographer and occasional filmmaker (agmin.org).

Listen to Jeremy Del Rio’s sermon “Vision for a New Day” at podcasts.charismamag.com

Voices of Justice

Keith Green Not one to mince words in God’s defense, Green wrote numerous songs that called out fellow Christians, challenging them to action

Sara Groves She has toured to benefit relief organization Food for the Hungry and the Christian human-rights group International Justice Mission

Jason Upton His songs can be raw, unpolished, unplanned. Critics call him a music artist to love or avoid. He says: “Most of my songs are prayers.”

Misty Edwards She writes many of her songs during times of spontaneous worship. “I think worship needs to change so we linger until we encounter God.”