But

almost 10 days after the first Spanish-speaking event in the United

States was held by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, ripples

are still being felt after hundreds of decisions were made in each of

three different services.

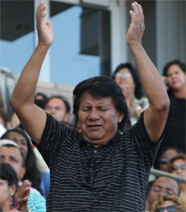

“It was quite an experience that a lot

of people are still talking about,” Festival Director Galo Vasquez said

from Los Angeles this morning. “People are very humbled with that

experience.

“The leaders have made the comment that they are sensing something unique has happened here.”

Unique to say the least.

A

total of 615 different Spanish-speaking churches throughout the Los

Angeles area partnered together for this weekend

evangelistic event, as the Hispanic church—commonly known as the

“Invisible Church”—finally started worked together, bringing over

18,000 people to the Home Depot Center in Carson, Calif.

“This

event has given them a new sense of identity. There is now a community

of Hispanics,” Vasquez said. “There hasn’t been cohesiveness as far as

the geographical location or the relationship between the churches.”

Hence, the “Invisible” tag.

But

it’s more than just a name, as Jose “Pepe” Caballero, the director of

the local committee, explains. It’s a perception that has affected

their reality.

“Hispanic pastors are not really recognized in

this city,” Caballero said. “If you ask the mayor, the police, any

authority in the city, they are not really recognized. They don’t take

them into account for anything that happens in the community.”

Part

of the complexities in the Los Angeles area is the diversity within the

Hispanic community. Just because a group of people speaks the same

language, doesn’t mean their cultures are naturally intertwined.

“Obviously

the Hispanic church has a subculture of its own,” Vasquez said. “Under

the subculture, there’s a national expression. You have the Mexicans,

the Guatemalans, the Argentinians, the Hondurans and so on. Their

culture is so strong. They fight to be themselves.”

Peeling back

the layers to the “Invisible Church” is complex. Each subculture has its

own defining elements, whether it’s food that binds the country or

a national flag flown, often proudly from a car window.

“We are proud of our food,” Caballero said. “We are very happy with our food. The food joins us together.”

But take a few more layers off and you’ll find that sometimes there’s a lack of depth that hinders spiritual unity.

“Even

amongst some of the pastors, they would rather not be known as

Christians, because they do not really have a strong testimony in the

city,” said Caballero, was in charge of involving the Hispanic Church

during the 2004 Billy Graham Rose Bowl Crusade. “That’s because the

pastors are not really trained to teach the Bible to these believers.”

So

follow-up becomes even more critical to a Festival such as this. And

that’s what Vasquez and his team are doing, matching up new Christians

with the appropriate churches.

“Making sure the church is proactive, inviting them to join their congregations,” Vasquez explains.

And

in many cases, that congregation is part of a larger American church,

split off and meeting on a Sunday afternoon or evening, or wherever they

can find space.

“It’s part of the human behavior that there’s a

conflict,” Vasquez said. “They wish they could afford a place of their

own so they could be themselves.”

And so more times than not, the church body lacks the attributes that keep it healthy and strong.

“Very few churches really get involved in the community,” Caballero

said. “It’s not like the people in the neighborhoods and the people in

the city go ‘Oh, what a beautiful Hispanic church we have here.'”

But those attitudes are starting to change. The importance of a church

building of their own, or having the same heritage, is fading into the

background as the unification of the Hispanic church is inching toward

prominence.

One sign of that unity is a major pastor’s

leadership meeting scheduled for July 30 to discuss what they learned

from the Festival de Esperanza process and to start planning for the

future.

“That’s an indication of how much they appreciated what

was accomplished in bringing them together and giving them a fresh

vision,” Vasquez said. “They talked a lot about the training that went

on to share their faith in Christ.”

But solidifying the Hispanic

church most effectively was the hundreds that flooded down the aisles

to the field to accept Christ as personal Savior. Witnessing that

life-changing power of the Gospel has transformed their definition of

church unity and what it means to work together as a local church body.

“All of us witnessed the expressions of the people who came forward by

friends and relatives,” Vasquez said. “The response was very moving.”

Used with permission from the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.