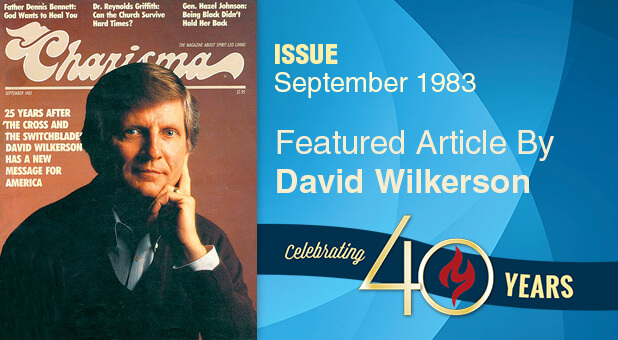

Note: The skinny 27-year-old Pennsylvania preacher’s call from the Lord was clear, but incredibly unexpected. Thousands of lives were to be changed in the next 25 years. Here, in this condensation of the opening chapter of the best-selling The Cross and the Switchblade is the story of how it started.

This whole strange adventure got its start late one night when I was sitting in my study reading Life magazine and turned a page. At first glance, it seemed that there was nothing on the page to interest me. It carried a pen drawing of a trial taking place in New York City, 350 miles away. I’d never been to New York and I never wanted to go, except perhaps to see the Statue of Liberty.

I started to flip the page over. But as I did, my attention was caught by the eyes of one of the figures in the drawing. A boy. One of seven boys on trial for murder. The artist had caught such a look of bewilderment and hatred and despair in his features that I opened the magazine wide again to get a closer look. And as I did, I began to cry.

“What’s the matter with me?” I said aloud, impatiently brushing away a tear. I looked at the picture more carefully. The boys were all teenagers. They were members of a gang called the Dragons. Beneath their picture was the story of how they had gone into Highbridge Park in New York and brutally attacked and killed a 15-year-old polio victim named Michael Farmer. The seven boys stabbed Michael in the back seven times, then went away wiping blood through their hair, saying, “We messed him good.”

The story revolted me. It turned my stomach. In our little Pennsylvania mountain town such things seemed mercifully unbelievable. That’s why I was dumbfounded by a thought that sprang suddenly into my head—full-blown, as though it had come into me from somewhere else.

Go to New York City and help those boys.

I laughed out loud. “Me? Go to New York? A country preacher barge into a situation he knows less than nothing about?”

Go to New York City and help those boys. The thought was still there, vivid as ever, apparently completely independent of my own feelings and ideas.

“I’d be a fool. I know nothing about kids like that. I don’t want to know anything.”

It was no use. The idea would not go away: I was to go to New York, and furthermore I was to go at once, while the trial was still in progress.

I felt uneasy, as though I had received orders but could not make out what they were.

“What are you saying to me, Lord?”

I walked around the study, seeking to understand what was happening to me. Each time I came to the desk my attention was drawn to that magazine.

I sat down in my brown leather swivel chair and with a pounding heart, as if I were on the verge of something bigger than I could understand, I opened the magazine. A moment later I was looking at the drawing and tears were streaming down my face.

The next night was Wednesday prayer meeting at church. It turned out to be a cold, snowy mid-winter evening. Not many people showed up; the farmers, I think, were afraid of being caught in town by a blizzard. Even the couple dozen townspeople who did get out straggled in late and tended to take seats in the rear, which is always a bad sign to a preacher; it means he has a “cold” congregation to speak to.

I didn’t even try to preach a sermon that night. When I stood I asked everyone to come down close “because I have something I want to show you,” I said. I opened Life and held it down for them to see.

“Take a good look at the faces of these boys,” I said. And then I told them how I had burst into tears and how I had got clear instruction to go to New York, myself, and try to help those boys. My parishioners looked at me stonily. I was not getting through to them at all, and I could understand why. Anyone’s natural instinct would be aversion to those boys, not sympathy. I could not understand my own reaction.

Then an amazing thing happened. I told the congregation that I wanted to go to New York, but I had no money. In spite of the fact that there were so few people present and in spite of the fact that they did not understand what I was trying to do, my parishioners silently came forward that evening and one by one placed an offering on the Communion table. The offering amounted to $75, just about enough to get to New York City and back by car.

Thursday I was ready to go. I had telephoned my wife, Gwen, who was visiting her parents, and explained to her—rather unsuccessfully, I’m afraid—what I was trying to do.

“You really feel this is the Holy Spirit leading you?” Gwen asked.

Yes, I do, honey.”

Well, be sure to take some good warm socks.”

Miles Hoover, the youth director from the church, and I came into the outskirts of New York along Route 46, which connects the New Jersey Turnpike with the George Washington Bridge. Once again logic was raising difficulties. What was I going to do once I got to the other side of the bridge? I didn’t know.

We needed gasoline, so we pulled into a station just short of the bridge. While Miles stayed with the car, I took the Life article, went into a phone booth and called the district attorney named in the article. When I finally reached the proper office, I tried to sound like a dignified pastor on a divine mission. The prosecutor’s office was not impressed.

“The district attorney will not put up with any interference in this case. Good day to you, sir.”

And The Line Went Dead

One hundred Court Street is a mammoth, frightening building to which people flock who are angry with each other and want vengeance. It attracted hundreds every day who have legitimate business there, but it also draws curious, gawking spectators who come to share—without danger—in the anger. One man in particular was sounding off outside the courtroom where the Michael Farmer trial was to be reconvened later in the morning.

“Chair’s too good for them,” he said to the public in general. He turned to the uniformed guard stationed outside the closed door. “Got to teach them a lesson, young punks. Make an example out of them.”

The guard hooked his thumbs in his belt and turned his back on the man, as if he had long ago learned that this was the only defense against the self-appointed guardians of justice. By the time we arrived—at 8:30 a.m.—there were 40 people waiting in the line to enter the courtroom. I discovered later that there were 42 seats available that day in the spectator section. I have often thought that if we’d stopped for breakfast, all that has happened to me since that morning of February 28, 1958, would have taken a different direction.

For an hour and a half we stood in line, not daring to leave, since there were others waiting for a chance to step into our places. Once, when a court official passed down the line, I pointed to a door farther along the corridor.

“Is that Judge Davidson’s chambers?” I asked him.

He nodded.

“Could I see him, do you think?”

The man looked at me and laughed. He didn’t answer, just gave a grunt that was half scorn, half amusement, and walked away.

At around ten o’clock a guard opened the courtroom doors and we filed into a little vestibule where each one of us was briefly inspected. We held out our arms; I took it they were looking for weapons.

“They’ve threatened the judge’s life,” said the man in front of me, turning around while he was being searched. “The Dragon gang. Said they’d get him in court.”

Miles and I took the last two seats. I found myself next to the man who thought that justice should be faster. “Those boys should be dead already, don’t you think?” he said to me even before we were seated, and then turned to ask his other neighbor the same question before I had a chance to answer.

I was surprised at the size of the courtroom. I had expected an impressive room with hundreds of seats, but I guess that idea had come from Hollywood. Actually, half of the room was taken up by court personnel, another fourth by the press, with only a small section in the rear for the public.

Then the boys themselves came in.

I don’t know what I’d been expecting. Men, I suppose. After all this was a murder trial, and it had never really registered with me that children could commit murder. But these were children. Seven stooped, scared, pale, skinny children on trial for their lives for a merciless killing. Each was handcuffed to a guard and each guard, it seemed to me, was unusually husky, as if he had been chosen deliberately for contrast.

The seven boys were escorted to the left of the room, then seated and the handcuffs taken off.

“That’s the way to handle them,” said my neighbor. “Can’t be too careful. God, I hate those boys!”

“God seems to be the only one who doesn’t,” I said.

“Wha … ?”

Someone was pounding on a piece of wood and calling the court to order as in walked the judge, very briskly, while the entire room stood.

I watched the proceedings in silence. And then, quite suddenly, it was over. It took me by surprise—which may, in part, explain what happened next. I didn’t have time to think over what I was going to do.

I saw Judge Davidson stand and announce that the court was adjourned. In my mind’s eye I saw him leaving that room, stepping through that door and disappearing forever. It seemed to me that if I didn’t see him now, I never would.

I’m going up there and talk to him,” I whispered to Miles.

“You’re out of your mind!”

“If I don’t … ” The judge was gathering his robes together, preparing to leave. With a quick prayer I grasped my Bible in my right hand, hoping it would identify me as a minister, shoved past Miles into the aisle, and ran to the front of the room.

“Your Honor!” I called.

Judge Davidson whirled around, annoyed and angry at the breach of court etiquette.

“Your Honor, please would you respect me as a minister and let me have an audience with you?”

But by now the guards had reached me. I suppose the fact that the judge’s life had been threatened was responsible for some of the roughness that followed. Two of them picked me up by the elbows and hustled me up the aisle, while there was a sudden scurrying and shouting in the press section as photographers raced each other to the exit trying to get pictures.

The guards turned me over to two blue uniforms, out in the vestibule.

“Close those doors,” ordered one officer. “Don’t let anyone out of there.”‘

Then, turning to me, “All right, Mister. Where’s the gun?”

I assured him that I didn’t have a gun.

They escorted me brusquely out to the corridor. There a semicircle of newsmen were waiting with their cameras cocked. One man asked me:

“Hey, Rev’rn. What’s that book you got there?”

“My Bible.”

“You ashamed of it?”

“Of course not.”

“No? Then why you hiding it? Hold it up where we can see it.”

And I was naive enough to hold it up. Flashbulbs popped, and suddenly I knew how it would come out in the papers: a Bible-waving country preacher, with his hair standing up on his head, interrupts a murder trial.

As soon as they let us go, we hurried to the parking lot where our car had earned another $2 charge. Miles didn’t say a word. The minute we got in the car and closed the door, I bowed my head and cried for 20 minutes.

“Let’s go home, Miles. Let’s get out of here.”

Going back over the George Washington Bridge, I turned and looked once more at the New York skyline. Suddenly I remembered the passage from Psalms that had given us so much encouragement: “They that sow in tears shall reap in joy.”

What kind of guidance had that been? I began to doubt there was such a thing as getting pinpointed instructions from God.

How would I face my wife, my parents, my church? I had stood before the congregation and told them that God had moved on my heart, and now I must go home and tell them that I had made a mistake and that I did not know the heart of God at all.

Then a strange thing happened.

In my nightly prayer sessions, one particular verse of Scripture kept occurring to me. It came into my mind again and again: “All things work together for good to them that love God and are called according to His purpose.”

It came with great force and a sense almost of reassurance, though to the conscious part of my mind nothing reassuring was conveyed. But along with it came an idea so preposterous that for several nights. I dismissed it as soon as it appeared.

Go back to New York.

When I had tried ignoring it three nights in a row and found it as persistent as ever, I set about to deal with it. This time, I was prepared.

New York, in the first place, was clearly not my cup of tea. I just did not like the place, and I was manifestly unsuited for life there. I revealed my ignorance at every turn, and the very name “New York” was for me now a symbol of embarrassment. It would be wrong from every point of view to leave Gwen and the children again so soon. I was not going to drive eight hours there and eight hours back for the privilege of making a fool of myself again. As for going back to the congregation with a new request for money, it was out of the question. These farmers and mine workers were already giving more than they should. How would I explain it to them, when I myself did not begin to understand this fresh order to return to the scene of my defeat? I had no better chance than before to see those boys. Less—because now I was typed in the eyes of city officials as a lunatic. Wild horses couldn’t drag me to my church with such a suggestion.

And yet, so persistent was this new idea, that on Wednesday night, I stood in the pulpit and asked my parishioners for more money to get me back to New York.

The response of my people was amazing. One by one, they again got up on their feet, marched down the aisle and placed an offering on the Communion table. This time, there were many more people in the church, perhaps 150. But the interesting thing is that the offering was almost exactly the same. When the dimes and quarters, and the very occasional bills, were all counted, there was just enough to get to New York again. Seventy dollars had been collected.

The next morning Miles and I were on our way by six. We took the same route, stopped at the same gas station, took the bridge into New York. Crossing the bridge, I prayed, “Lord, I don’t have the least idea why You let things, happen as they did last week or why I am coming back into this mess. I do not ask to be shown Your purpose, only that You direct my steps.”

Once again we found Broadway and turned south along this only route we knew. We were driving slowly along when suddenly I had the most incredible feeling that I should get out of the car.

“I’m going to find a place to park,” I said to Miles. “I want to walk around for a while.” We found an empty meter.

“I’ll be back in a while, Miles. I don’t even know what it is I’m looking for.”

I left Miles sitting in the car and started walking down the street. I hadn’t gone half a block before I heard a voice:

“Hey, Davie!”

I didn’t turn around at first, thinking some boy was calling a friend. But the summons came again.

“Hey, Davie. Preacher!”

This time I did turn around. A group of six teenage boys was leaning against the side of a building beneath a sign saying, “No Loitering. Police Take Notice.” They were dressed in tapered trousers and zippered jackets. All but one of them were smoking, and all of them were bored.

A seventh boy had separated himself from the group and walked after me. I liked his smile as he spoke.

“Aren’t you the preacher they kicked out of the Michael Farmer trial?”

“Yes. How’d you know?”

“Your picture was all over the place. Your face is kind of easy to remember.”

“Well, thank you.”

“It’s no compliment.”

“You know my name, but I don’t know yours.”

“I’m Tommy. I’m the president of the Rebels.”

I asked Tommy, president of the Rebels, if those were his friends leaning against the “No Loitering” sign, and he offered to introduce me. They kept their studiously bored expressions until Tommy revealed that I had had a run-in with the police. That was magic with these boys. It was my carte blanche with them. Tommy introduced me with great pride.

“Hey fellows,” he said, “here’s the preacher who was kicked out of the Farmer trial.”

One by one, the boys unglued themselves from the side of the building and came up to inspect me. Only one boy did not budge. He flicked open a knife and began to carve an unprintable word in the metal frame of the “No Loitering” sign. While the rest of us talked, two or three girls joined us.

Tommy asked me about the trial, and I told him I was interested in helping teenagers, especially those in the gangs. The boys, all but the carver, listened attentively, and several of them mentioned that I was “one of us.”

“What do you mean, I’m one of you?” I asked.

“Their logic was simple. The cops didn’t like me; the cops didn’t like them. We were in the same boat, and I was one of them. This was the first time but by no means the last time that I heard this logic. Suddenly I caught a glimpse of myself being hauled up that courtroom aisle, and it had a different light on it. I felt the little shiver I always experience in the presence of God’s perfect planning.

I didn’t have time to think more about it just then, because the boy with the knife at last stepped up to me. His words, although they were phrased in the language of a lonesome boy on the streets, cut my heart more surely than his knife would have been able to do.

“Davie,” the boy said. He hiked his shoulder up to settle his jacket more firmly on his back. When he did, I noticed that the other boys moved back a fraction of a step. Very deliberately, this boy closed and then opened his knife again. He held it out and casually ran the blade down the buttons of my coat, flicking them one by one. Until he had finished this little ritual, he did not speak again.

“Davie,” he said at last, looking me in the eye for the first time, “you’re all right. But Davie, if you ever turn on boys in this town … ” I felt the knife point press my belly lightly.

“What’s your name, young man?” His name was Willie, but it was another boy who told me.

“Willie, I don’t know why God brought me to this town. But let me tell you one thing. He is on your side. That I can promise you.”

Willie’s eyes hadn’t left mine. But gradually I felt the pressure of the knifepoint lessen.