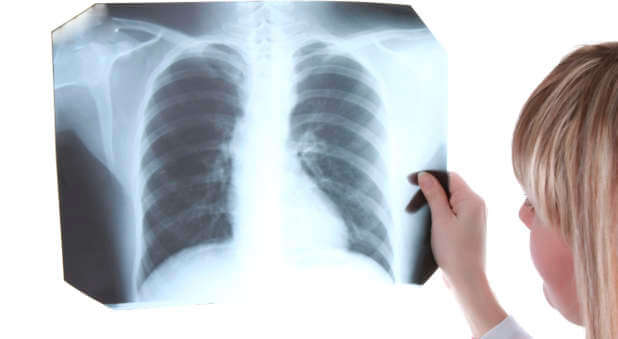

More than 3 million Americans suffer from advanced emphysema, the nation’s third-leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer.

Until recently, there was little doctors could do to help them other than perform major surgery to remove the diseased portion of their lungs or give them a full-blown lung transplant.

Now there is new hope. It’s a tiny metal device known as the Lung Volume Reduction Coil (LVRC).

“We think this is going to be a game-changer for patients with advanced emphysema,” says Charlie Strange, M.D., pulmonologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

When LVRCs are implanted in patients’ lungs, they compress diseased tissue and allow healthy tissue to function more efficiently.

Because the coils reduce lung volume by up to 30 percent, restore the lungs’ natural elasticity, and open up the small airways, they counteract emphysema’s hallmark symptom: shortness of breath.

Although emphysema has been linked to air pollution and workplace dust, most cases are caused by years of heavy smoking. In people with advanced emphysema, extreme shortness of breath is brought on by hyperinflation, a process in which excess air is trapped in the lungs and is almost impossible to exhale.

Until the advent of LVRCs, patients who no longer responded to conventional treatments such as rehabilitation exercises, medications, and supplemental oxygen had only two invasive and risky options: lung volume reduction surgery to remove diseased tissue or a lung transplant.

LVRC treatment is minimally invasive and can be performed on an outpatient basis. There are few, if any, side effects.

“Even in the first few hours, most patients notice that they can breathe a little bit easier,” Dr. Strange tells Newsmax Health.

In Europe, LVRC treatment has been approved since 2008. In the U.S., researchers are evaluating the treatment as part of the FDA-approved RENEW Study. Dr. Strange is the principal investigator.

To participate, patients must have severe emphysema, have difficulty with daily activities, completed a pulmonary rehabilitation program, and stopped smoking for at least eight weeks.

“We’re taking the worst of the worst patients and improving them,” says Dr. Strange.

If you or someone you know might benefit from LVRC, Google “renew study” and go to the National Institutes of Health’s clinicaltrials.gov site to find out how to apply for enrollment. A patient’s doctor also may be able to facilitate enrollment.

Dr. Strange is hopeful the American study will mirror other research which shows LVRC treatment is safe, effective, and offers dramatic improvements in lung function. He is optimistic that the FDA will eventually approve LVRCs in the U.S.

About 15 million Americans have emphysema. But many patients with mild-to-moderate disease probably won’t need LVRC treatment.

Meanwhile, Dr. Strange is seeing remarkable improvements in patients with advanced disease. Some of his patients have been able to come off of supplemental oxygen. At least one has returned to work.

One of his most rewarding cases was a man who went on local television to announce that LVRC treatment allowed him to do something he previously thought impossible: walk his daughter down the aisle for her wedding.

“This is one of those heartwarming stories that we’d like to see more of in medicine,” says Dr. Strange, who’s proud to have restored such patients to a near-normal life while sparing them the agony of lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation.

“It’s been a labor of love,” he says.

For the original article, visit newsmaxhealth.com.